“The [design] concept came out of the idea that the Ethics Center wanted to become integral to a fairly unique site,” said Andrew Herdeg, AIA of Lake Flato Architects in San Antonio, TX, who served as the design firm for the project. “It needed to blend in with the context of the site.”

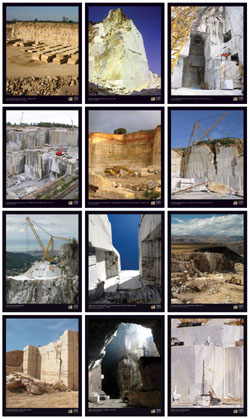

The abandoned quarry was acquired by the University in 2003, and the land was developed into a Nature Park, which encompasses 500 acres and includes several miles of hiking trails, field research in a variety of ecological habitats, wetlands and prairie restoration. The site features many cliffs, unpredictable terrain and ponds as well as being bordered by Big Walnut Creek to the west.

“It is a beautiful site,” said Herdeg. “The notion to use native limestone in its most native and rustic form seems very appropriate. It grounds the building to the site.”

The architect explained that the University’s academic community expressed some concern about not wanting the building to stand out. “They wanted it to be a showpiece for the University, but not a visual showpiece within the quarry,” he said. “We used limestone and natural wood, and kept the scale [of the building] low so that it fit in with the landscaping.”

Herdeg went on to say that using a native limestone in the design of the structure was a decision made from the start of the project. “In general, we try to use materials of the region to connect the building back to the place, and also for sustainable issues such as minimizing energy,” he said. “The limestone in Texas is much softer. It often comes in a cream or buff color, and there are grays and whites, but none are as hard as those found in Indiana. We were intrigued.”

Utilizing Roughbacks

The limestone chosen for the Prindle Institute for Ethics was supplied by Bybee Stone Co. Inc. of Bloomington, IN. Approximately 4,200 cubic feet of variegated roughbacks was employed for the job.Will Bybee of Bybee Stone explained that roughbacks are the remnant pieces that are left after a slab is cut. “Blocks that come out of the quarry have two rough sides normally,” he said. “When sawing up a block, most of the time roughbacks will be waste. They usually have a lot more coloring and a very rough surface. It goes in and out - sometimes dramatically.”

The blocks of limestone used for the project were cut on gangsaws at Bybee Stone’s facility. “For us, the nice thing was not to throw away [any of the stone],” said Bybee. “We had done similar kinds of work with roughbacks in the past, so we felt fairly comfortable. As the job went forward, we needed a little more instruction. It was very random. There was no constancy at all, except not having constancy.”

Both Bybee and the architect explained that mock-ups were done prior to the stone installation. “Mock-ups were critical because this was an experiment for us,” said Herdeg. “We had to see how the roughness would relate or translate to a larger scale. A lot of the blocks had significant projections at the edge - adjoining blocks would have an 8-inch differential between each. That much of an offset begins to accentuate the block. We wanted it to be more monolithic. [The building] was meant to mimic the sides of an old quarry.

“We also had to understand how the joints would work,” Herdeg went on to say. “[The roughbacks] were laid up as a dry stack. We had to see how big the joint needed to be. We kept the joints tight.”

According to Bybee, the mock-up process also proved valuable for his team. “We got an explanation through the mock-ups of what the architect wanted for the design,” he said. “We had to cut back a little farther than we would [normally] for a roughback so we could get a setting bed. Because of the ‘in and out’ of the roughback, it becomes an issue. Some of the stones overhang, and others don’t.”

Bybee said that one of the most challenging aspects of the project was stocking enough roughbacks. “Every block can only get two slabs out of it,” he explained. “The biggest challenge was getting enough roughbacks out of our normal saw process. We started months before collecting them. That had to be taken into consideration.”

Meeting LEED Standards

In total, construction of the Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics took about one year to complete. It took Bybee Stone approximately four months to complete the stone fabrication.“It was a really challenging project,” said Herdeg. “Accessibility to the site was an issue, and the foundation was complicated. [And] the building itself had its own complications in terms of design. It was spread out to keep the scale low. [But] in the end, we were very happy with it. Bybee and the contractor did a great job.”

Upon completion, the building received LEED Gold from the U.S. Green Building Council. It was the first LEED project in Indiana, and it won the highest design award given by the Indiana chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) the year construction finished, according to Herdeg, adding that points were earned for using regional stone in the project’s design.

According to the DePauw University, “the Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics promotes critical reflection and constructive debate about the most important ethical questions: What is right, just and good, and what must human beings do - now and in the future - to meet their moral responsibilities? The Institute seeks to explore with DePauw University students the moral challenges of the 21st Century and encourage them not to remain silent in the face of injustice.” Construction of the new facility, which sits at the highest point of the Nature Park, was funded by Janet W. Prindle, Class of 1958.

The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics

DePauw University

Greencastle, IN

Architect of Record: CSO Architects, Inc. Indianapolis, IN

Design Architect: Lake Flato Architects, San Antonio, TX

General Contractor: Shiel Sexton, Indianapolis, IN

Stone Supplier: Bybee Stone Co., Inc., Bloomington, IN

Stone Mason: Dodds Masonry Construction Inc., Mooresville, IN