“The new Center for Art and Education is designed to be part of an ensemble of entry buildings,” explained architect Steven Gerrard of Ann Beha Architects in Boston, MA. “With the historic round barn and the admissions building/museum shop, the Center frames the gateway to the Museum experience — playing a critical role in visitor orientation. A less ‘familiar’ design — interlocking forms, deep eaves, flat roof and a glass curtain wall — grew from exchange with clients and donors, shifting expectations from traditional design to a contemporary vocabulary.”

Gerrard went on to say that the design responds to two settings — one facing Vermont’s heavily traveled Route 7 and the other facing the enclave of historic buildings. “The natural roll in the landscape allowed the building to present itself in two different scales,” he said. “The side facing Route 7 is two stories and announces the Museum and its activities to the community in a striking new way. The side facing the campus offers a one-story structure with a long welcoming porch, respecting and relating to the scale of the surrounding historic buildings.”

According to the architect, the building’s massing interlocks two elements: the exhibition galleries and the education studio and auditorium, joined by a central lobby gallery. “The Center is organized on two levels, connected by a grand stair,” explained Gerrard. “On the upper level, galleries are lit from lay-lights and clerestories, and an auditorium, used for gatherings and programs, opens onto a porch. The lower level provides additional galleries and a classroom opening onto an outdoor terrace.”

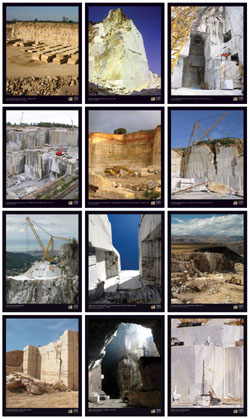

Choosing local stone

From the outset it was decided that regional stone would be used in the design of the new Pizzagalli Center. “The new Museum is located in a campus of historic vernacular structures that display the tradition and craft of local materials — particularly stone and wood,” said Gerrard. “It was important for the building to express this materiality in a fresh and contemporary manner. Being a LEED project, local materials were also incorporated to reduce required transportation of building materials and to support the local economy.”

Chip Stulen, Director of Buildings, Ticonderoga Curator at the Shelburne Museum, agreed that using local materials was a top priority. “It was important to have a building that essentially represents the region to people who come to Vermont to visit or live here,” he said. “We wanted something that would read to them as local material — and materials with integrity. The interesting thing about stone is that the aesthetic of how it is incorporated into a building is personal. We started with some mock-ups of the stonework and other materials for the principal people, such as the board members, to get involved. It was very important for them to see it three dimensionally — that was a critical component in the whole process, and the architects encouraged it. “

|

Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education Shelburne Museum Shelburne, VT |

|

Architect: Ann Beha Architects, Boston, MA Construction Manager: PC Construction, South Burlington, VT Stone Quarriers: Sheldon Slate, Middle Granville, NY (Vermont slate); Champlain Stone Ltd., Warrensburg, NY (American GraniteTM Ashlar) Stone Supplier/Installer: Barre Tile and Stone Shop, South Barre, VT (slate) Stone Mason: North Stars Masonry, Inc. (granite) Installation Products: Laticrete International, Bethany, CT (thinset and grout); Schulter Systems, Plattsburgh, NY (crack suppressant system) |

Additionally, Stulen explained that the sustainability aspect was also a significant component of the new building’s design. “It was very important to us,” he said. “To use local materials helps to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Stone is featured as both a wall material and as interior flooring. “The wall stone is ashlar stacked granite, quarried in the nearby Adirondack Mountains [by Champlain Stone of Warrensburg, NY],” said Gerrard. “This particular granite was selected for its range of color and texture — blue-gray with striations of white quartz combined with weathered hand-split faces featuring red earth tones.”

The particular granite supplied by Champlain Stone was American GraniteTM Ashlar, which has a natural split-face finish to show the natural grain of the stone as it was formed. Approximately 170 tons of the material was furnished for the project, with pieces ranging from 4 x 12 inches in height, and 3 to 5 inches in thickness. Each piece has a facing area ranging from ¼ to 2 square feet.

The American Granite Ashlar stone was also employed for inside the building. “The interior reintroduces the exterior materials, including granite wall masonry, slate flooring and cedar siding,” said the architect. “The slate floor is a Vermont mottle purple and green with a natural cleft surface. The grand stair incorporates continuous slate treads of 6 to 8 feet long. The slate was selected for its rich range of color, durability and the client’s desire to feature a local natural material.”

In total, 2,300 square feet of Vermont Mottled purple slate — quarried by Sheldon Slate of Middle Granville, NY, and supplied by Barre Tile and Stone Shop of South Barre, VT — was used for the interior design. The pieces measured 18 x 18, 12 x 18 and 6 x 18 inches.

Reviewing mock-ups

Although the architects did not visit the quarries, time was dedicated to reviewing the stone before it was installed. “We did not visit a quarry for this project, but we did visit a series of buildings completed by the stone subcontractor to review both the stone and the quality of masonry work,” explained Gerrard. Champlain Stone provided a mock-up of the American Granite Ashlar for the architect’s approval on the jobsite.

“For the slate floor, we reviewed the mock-ups for color range, natural texture and pattern, and cleft surface finish,” said the architect. “We specified the slate as mottled purple and green Vermont Slate. During the mock-up process we requested the mix of stone featuring the full range of the material’s color. It was the design intent to have the stone floor very textured and colorful.”

Both Gerrard and installer Tom Burke of Barre Tile and Stone Shop agreed that the most challenging aspect of the stonework was the slate staircase. “The stairs were the most challenging, due to the unevenness of the concrete base,” said Burke. “We had to level the base by grinding and flashing to keep the tread and risers within code tolerance.”

Gerrard added that “to reduce the potential for cracking and to even out the surface of the concrete we introduced a Ditra crack suppressant system [from Schluter Systems of Plattsburgh, NY] under the slate.” Additionally, Laticrete 253 and 254 thinset as well as Laticrete Permacolor grout — all from Laticrete International of Bethany, CT — was used to set the slate floor.

The slate floor installation took a total of six days, while it took two weeks to install the stairs. A crew of four laid the slate flooring, while three additional men worked on the stairs.

“I visited the site a couple of times during the flooring installation,” said Gerrard. “The construction manager, PC Construction, did an excellent job coordinating the installation of the slate.”

With the introduction of the Pizzagalli Center for Art and Education, the Shelburne Museum is now open yearround. Until now, it had only operated seasonally. “The community has been very excited about the project,” said Gerrard.